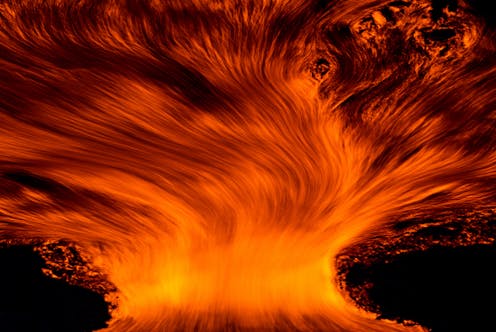

Donald Trump’s anger has been building and now seems volcanic. Abstract Aerial Art/Getty Images

The Greek divinity Nemesis, rarely depicted in art, has no place in the Olympian pantheon of a dozen gods and goddesses. But she’s an omnipresent force of retribution, an implacable force of punishment that arrives, if not sooner, then later.

Nemesis can bide her time for generations, but there’s no escaping her.

So too, it seems, with President Donald Trump, who is “clearly not a man who discards his grudges easily,” William Galston of the Brookings Institution said recently. This observation is an understatement.

Trump’s resentment has been steaming since the 2020 presidential election. Now that he is again president, he’s far from appeased; his ire is boiling over.

“Flooding the zone,” a term borrowed from football, was former Trump adviser Steve Bannon’s way of describing the Trumpian tactic of issuing a barrage of statements whose sheer pace and multiplicity, not to mention contents, are intended to stymie any impulse at rational response.

As he has gained fame and power, Trump’s contemptuous rage at his opponents and his appetite for vengeance appear to have sharpened.

Like Nemesis, Trump is now pursuing his perceived enemies, using the power of the presidency. Among his recent retribution: He has

fired Department of Justice officials and staff who worked on criminal investigations and prosecutions of him; he has revoked security clearances for intelligence officials to “punish his perceived opponents,” as one news story put it. And he has removed the portrait of Gen. Mark Milley from the Pentagon wall that traditionally features portraits of the retired chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as Milley was. In 2024, journalist Bob Woodward reported that Milley had told him, “No one has ever been as dangerous to this country as Donald Trump. Now I realize he’s a total fascist. He is the most dangerous person to this country” – clearly sparking Trump’s ire.

As a poet and student of the classics, my impulse is to find analogs for this behavior, this temperament – precedents that might help provide some perspective.

Trump displays his anger during a rally on Nov. 3, 2024, in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

Tyrants, heroes and horses

Historians, I thought, would be able to come up with analogs. For example, Trump’s initial choice of a political ally, Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz, as attorney general – widely seen as unqualified for the post and who later withdrew – was likened to the Roman emperor Caligula, who made his horse a senator. Figures from Greek history, from the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus to Alexander the Great, could be famously power-hungry and vindictive.

Classical epic and drama furnish plenty of rage, which is the first word of the Homeric epic “The Iliad.”

Since epic and tragic heroes are in positions of power, temperament and action mesh. The Greek hero Achilles’ clash with the Greek army’s commander Agamemnon at the outset of “The Iliad” is psychologically plausible. Each man feels insulted and slighted by the other; both have cause for resentment.

Achilles nurses his rage at all his fellow Greeks until, much later in the epic, his grief at the death of his beloved Patroklos sends him back into battle. This larger-than-life hero is vulnerable, changeable and human.

Perhaps the most famous example of vengeance in Greek tragedy is Aeschylus’ trilogy, “The Oresteia.” When Clytemnestra murders her husband, Agamemnon, on his return from Troy, she has three comprehensible motives. Agamemnon has sacrificed their daughter; he has brought home a mistress, Cassandra; and Clytemnestra feels loyalty, both personal and political, to Aegisthus, her husband’s cousin, whom she has taken as a lover in her husband’s absence and who has his own reasons for hating Agamemnon.

So vindicated does Clytemnestra feel in having murdered Agamemnon – and Cassandra as well – that she proudly compares her action to rain that fertilizes the crops. As rain is part of the cycle of the seasons, her act has righted the balance of justice.

Agamemnon was murdered in cold blood by Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, in vengeance for Iphigenia’s death and all the grief he’d given them both.

Flaxman, artist, from The Print Collector/Getty Images

Cunning rage leads to death

Turning to a few of Shakespeare’s more vengeful characters, Iago in “Othello” is an embodiment of a cunning rage that leads him to systematically destroy the innocent Othello’s marriage. He does this by falsely hinting – and then planting a chain of evidence suggesting – that Othello’s bride, Desdemona, is unfaithful.

Othello eventually kills both Desdemona and himself. But the Romantic critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge famously referred to Iago’s “motiveless malignancy,” since it’s hard to be sure exactly why Iago is so set on destroying Othello.

Hamlet himself is a reluctant avenger who keeps putting off the act of revenging his father’s murder. In the history play named for him, Richard III’s resentment, going back to having been a deformed and unloved child, makes more sense. Richard lusts after power; he systematically and clandestinely murders his own brother and nephews, who would stand between him and his elder brother Edward’s throne.

Whether motivated by political ambition, generalized rancor or an inherited assignment, none of these figures ends well. They all have enemies, and they all – except Iago, who will be tortured and executed – die on stage. All have done plenty of damage; none survives long to feel vindicated. Even Clytemnestra’s triumph is short-lived, since her own son, Orestes, will soon avenge his father’s death by murdering his mother – Clytemnestra.

But all these figures seem to feel personal passion. Even the opaque Iago has one chief target: Othello. They don’t present compelling parallels to Trump, whose anger appears to be simultaneously private and public.

Easily offended, Trump is quick to strike back with insults; but he also seems to have an insatiable appetite for broader and deeper punishment, meted out to more people and even after a lapse of time. Hence literary parallels are less than compelling.

Trump’s anger seems more general than personal. His aggrieved sense of having been wronged, victimized by his enemies, is a constant in his career. But his targets shift. One day it’s judges; another day it’s election officials. Yet another day, it’s the “deep state.”

And Trump’s implacable resentment has struck a chord among many Americans whose resentment has a more rational basis. Trump’s base may believe he is speaking for them – “I am your warrior. I am your justice,” he said in a speech at a conservative forum, but his first priority has always been himself.

A spirit, ranging for revenge

The damage done by Trump is often inflicted by others. Their threats, harassment and even violence are done in the name of Trump.

He has pardoned almost all of the Jan. 6 insurrectionists, some of whom have now boasted they will acquire guns.

Trump has removed government protection from figures who have dared to disagree with him and have received death threats, including Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Shakespeare, turning history into great poetry, comes to mind after all. In “Julius Caesar,” knowing that his funeral oration over the body of the assassinated Caesar will stir up an angry mob, Mark Antony muses:

“And Caesar’s spirit, ranging for revenge,

With Ate by his side come hot from hell,

Shall in these confines with a monarch’s voice

Cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the dogs of war”

Antony imagines Caesar’s vengeful spirit rising from the underworld to incite further violence. Not only will Caesar’s assassins be punished, but the hell of civil war will be let loose to cause widespread suffering. Precisely who Trump wants to punish appears secondary to his delight in releasing precisely those hellish dogs. Everyone is a potential enemy and a potential victim.

“I am your retribution,” Trump has said. Nothing in Trump’s continuing story more clearly echoes the classics than this ominous melding of self with a superhuman principle of revenge.

Such a merging of a mortal individual with a pitilessly abstract power like Nemesis is closer to myth than to history. Or so it would be comforting to assume.

Rachel Hadas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Contact Us

If you would like to place dofollow backlinks in our website or paid content reach out to info@qhubonews.com