Hurricane Milton went from barely hurricane strength to a dangerous Category 5 storm in less than 24 hours as it headed across the Gulf of Mexico toward Florida.

As its wind speed increased, Milton became one of the most rapidly intensifying storms on record. And with 180 mph sustained winds on Oct. 7, 2024, and very low pressure, it also became one of the strongest storms of the year.

Less than two weeks after Hurricane Helene’s devastating impact, this kind of storm was the last thing Florida wanted to see. Hurricane Milton was expected to make landfall as a major hurricane late on Oct. 9 or early Oct. 10 and had already prompted widespread evacuations.

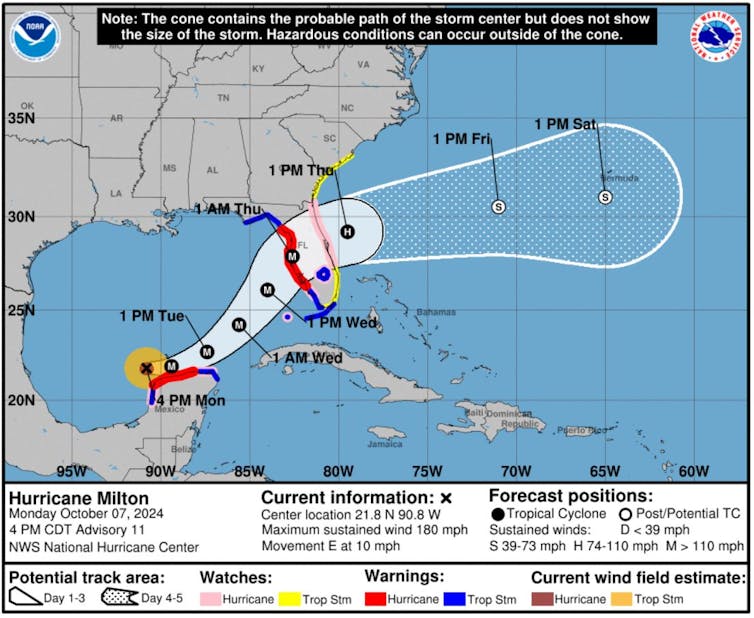

Hurricane Milton’s projected storm track, as of midday Oct. 7, 2024, shows how quickly it grew from formation into a major hurricane (M). Storm tracks are projections, and Milton’s path could shift as it moves across the Gulf of Mexico. The cone is a probable path and does not reflect the storm’s size.

National Hurricane Center

So, what exactly is rapid intensification, and what does global climate change have to do with it? We research hurricane behavior and teach meteorology. Here’s what you need to know.

What is rapid intensification?

Rapid intensification is defined by the National Weather Service as an increase in a tropical cyclone’s maximum sustained wind speed of at least 30 knots – about 35 mph within a 24-hour period. That increase can be enough to escalate a storm from Category 1 to Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

Milton’s wind speed went from 80 mph to 175 mph from 1 p.m. Sunday to 1 p.m. Monday, and its pressure dropped from 988 millibars to 911.

The National Hurricane Center had been warning that Milton was likely to become a major hurricane, but this kind of rapid intensification can catch people off guard, especially when it occurs close to landfall.

Hurricane Michael did billions of dollars in damage in 2018 when it rapidly intensified into a Category 5 storm just before hitting near Tyndall Air Force Base in the Florida Panhandle. In 2023, Hurricane Otis’ maximum wind speed increased by 100 mph in less than 24 hours before it hit Acapulco, Mexico. Hurricane Ian also rapidly intensified in 2022 before hitting just south of where Milton is projected to cross Florida.

What causes hurricanes to rapidly intensify?

Rapid intensification is difficult to forecast, but there are a few driving forces.

Ocean heat: Warm sea surface temperatures, particularly when they extend into deeper layers of warm water, provide the energy necessary for hurricanes to intensify. The deeper the warm water, the more energy a storm can draw upon, enhancing its strength.

Sea surface temperatures have been warm in the Gulf of Mexico, where Hurricane Milton was crossing just northwest of the tip of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula on Oct. 7, 2024. A temperature of 30 degrees Celsius is equivalent to 86 degrees Fahrenheit.

NOAA

Low wind shear: Strong vertical wind shear – a rapid change in wind speed or direction with height – can disrupt a storm’s organization, while low wind shear allows hurricanes to grow more rapidly. In Milton’s case, the atmospheric conditions were particularly conducive to rapid intensification.

Moisture: Higher sea surface temperatures and lower salinity increase the amount of moisture available to storms, fueling rapid intensification. Warmer waters provide the heat needed for moisture to evaporate, while lower salinity helps trap that heat near the surface. This allows more sustained heat and moisture to transfer to the storm, driving faster and stronger intensification.

Thunderstorm activity: Internal dynamics, such as bursts of intense thunderstorms within a cyclone’s rotation, can reorganize a cyclone’s circulation and lead to rapid increases in strength, even when the other conditions aren’t ideal.

Research has found that globally, a majority of hurricanes Category 3 and above tend to undergo rapid intensification within their lifetimes.

How does global warming influence hurricane strength?

If it seems as though you’ve been hearing about rapid intensification a lot more in recent years, that’s in part because it’s happening more often.

The annual number of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean that achieved rapid intensification each year between 1980-2023 shows an upward trend.

Climate Central, CC BY-ND

A 2023 study investigating connections between rapid intensification and climate change found an increase in the number of tropical cyclones experiencing rapid intensification over the past four decades. That includes a significant rise in the number of hurricanes that rapidly intensify multiple times during their development. Another analysis comparing trends from 1982 to 2017 with climate model simulations found that natural variability alone could not explain these increases in rapidly intensifying storms, indicating a likely role of human-induced climate change.

How future climate change will affect hurricanes is an active area of research. As global temperatures and oceans continue to warm, however, the frequency of major hurricanes is projected to increase. The extreme hurricanes of recent years, including Beryl in June 2024 and Helene, are already raising alarms about the intensifying impact of warming on tropical cyclone behavior.

Zachary Handlos receives funding from the National Science Foundation. He is affiliated with the American Meteorological Society as the incoming chair of their Board on Higher Education. He is also an academic faculty partner of the Georgia Climate Project.

Ali Sarhadi receives funding from NSF and Georgia Tech.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Contact Us

If you would like to place dofollow backlinks in our website or paid content reach out to info@qhubonews.com